Berlin is an interesting city to visit for many different reasons. With everything that Berlin has become known as in recent years- a hip city full of artists, street art, all nigh raves, and an international food scene- it is easy as an outsider to forget that for much of the last century Berlin was at the forefront of European and world history.

Germans, and Berliners in particular, have an interesting way of dealing with their pained history. In the United States we have the tendency to ignore the mistakes we’ve made in the past, to sweep such things under the rug, as though if we don’t face them then it never happened. Berliners seem to have the exact opposite approach.

Throughout the city there are somber reminders of the war that nearly destroyed the country, a genocide that killed millions, and the divided country and city that stood for 45 years. The prevailing attitude here is one of awareness. An attitude of “Germany has done some screwed up things in the past and we are going to acknowledge them and take responsibility for them and, most importantly, learn from them.”

One of the most obvious of these reminders is the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, a 4.7 acre site in the city center covered with 2,711 concrete slabs. The slabs are uniform in horizontal dimensions (in a shape that some say resemble coffins), but vary in height creating a somewhat dizzying effect. Designed by American architect Peter Eisenman and opened in 2005, the memorial hasn’t been without controversy.

Some have complained that it doesn’t include the word ‘holocaust’, while others are upset by the fact that it excludes the various other groups who were also targeted by the Nazis. There is also some confusion over the meaning of the memorial, or if there is any meaning at all. Eisenman once stated that the memorial was “designed to produce an uneasy, confusing atmosphere, and the whole sculpture aims to represent a supposedly ordered system that has lost touch with human reason”, but the official guidebook states “the design represents a radical approach to the traditional concept of a memorial, partly because Eisenman did not use any symbolism”. What the memorial represents, or doesn’t, and even though it is sometimes filled with teenagers running around and smoking cigarettes, it still remains a somber remembrance to the almost 6 million Jews who were killed by the Nazis.

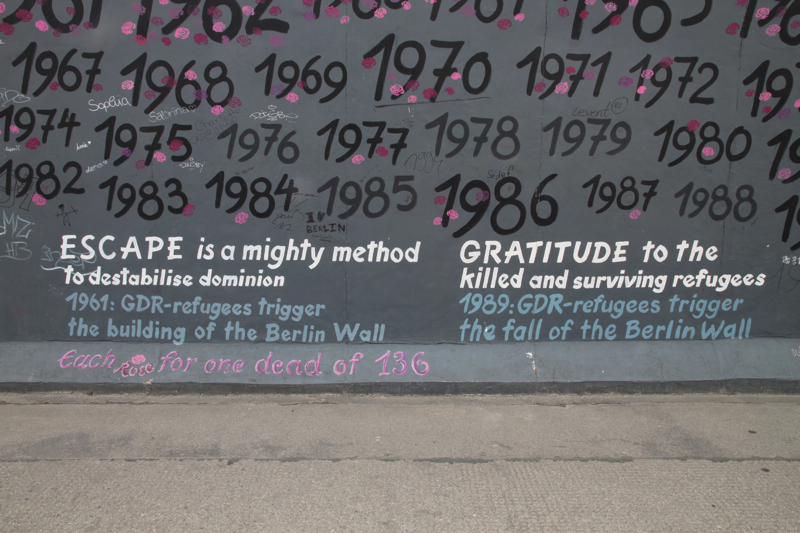

On August 13, 1961 the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) began constructing a wall that would divide the city for the next 28 years. Often referred to by the West German government as the “Wall of Shame”, the Berlin Wall stopped movement between the two parts of the country, separating families and cutting people off from their jobs. In September 1989 East Berliners started staging protests and on November 9 the Wall fell.

Today the wall is almost completely destroyed with only a few key parts still remaining. An 80 meter long piece stands at the Topography of Terror, the site of the former Gestapo headquarters, and the longest section, a 1.3 km stretch along Mühlenstrasse called the East Side Gallery, is covered with paintings from international artists representing hope, peace, and freedom.

The Reichstag building is another, possibly less obvious, reminder of the dark past of the country. The building was home to the German Parliament from 1894 until it was severely damaged in a fire in 1933. Though the fire was officially blamed on Marcus van der Lubbe, a Dutch communist, by the Nazi party as a way of showing the horrors of Communism to the German people, it is suspected by many that the fire was set by the Nazis themselves. The building was unused until after German reunification when reconstruction began in 1990.

Today a large glass dome, open to the public, sits atop the building. This dome provides a 360 degree view of Berlin, as well as a view into the debating chamber of Parliament below. Norman Foster, the English architect behind the project, built the dome as symbol of a democratic and united Germany.

The reminders are there. And though most of them now carry a message of peace, democracy, hopefulness for the future, it begs the question: can you ever really move on when tragic history is constantly staring you in the face?

It saddened me when I learned that many Germans, both young and old, don’t feel that they can be proud of their country. Germany has a rich history of philosophers, composers, inventors, and scientists. 101 Nobel Prize winners have come from Germany. The country has the world’s oldest universal health care system and the world’s fourth largest economy, which is even more impressive if you take into account that 70 years ago much of the country was completely destroyed.

There are many people who think that the atrocities of the past should never be far behind when speaking about Germany, and while I agree it is important to remember and speak about the harder parts of history, it is unfair to categorize an entire country by the mistakes of past generations. While I can’t speak for the people of a country where I’ve spent less than week total, I do hope that the rest of the world starts to look past the tragedies when Germany’s name is brought up and starts to see more of the triumphs.

What do you think about constant reminders of a troubled past?

That actually is really sad that Germans feel like they can’t be very patriotic. I remember someone telling me recently that it’s considered a bit trashy if you go around waving (or wearing) German flags. It’s really interesting actually.

Great post on such an interesting, confusing and important topic, Amanda. I really enjoyed it!

Jessica Wray recently posted..And Then It All Fell Apart

Thanks, Jess! I’ve heard that Spaniards are also not big into flags or any displays of patriotism (outside of soccer matches) because of Franco. Do you think that’s true?

I’ve been a regular reader of your blog for a while now, but never commented before. This time, though, your article touches a topic that I deem of great importance – as a Berliner. It was interesting to me to read how an outsider views our, I have to admit, indeed rather particular way of dealing with our past. There is one small factual error in your article, though: The Reichstag building was not unused before the 1990s, it was reconstructed for a first time in the 1960s and then used for exhibitions and meetings, just not for parliamentary sittings, as this was forbidden under the status of Berlin during the Cold War. I don’t know whether you did a tour of the building, or only visited the dome – a lot of the historical elements that can be seen today were actually covered up during the first reconstruction and forgotten about until they began working in the 1990s.

Thanks for the comment, Hannah. I am glad I didn’t offend you! And thank you for correcting me. I will change that in the post!

The Holocaust is a pretty hard thing to come back from, but Germany has certainly rebuilt itself financially.

Kate Peregrina recently posted..Translation Problem #004 – Masturbation, let’s not talk about it

They definitely have!

I guess I never realized Germans still felt that way. I met a german traveler while in Bombay, and along with some Dutch they talked about how (of course) the US is way worse that Germay, then the German told a concentration camp JOKE- something I never knew existed because I didn’t realize people could be so cruel- in their eyes Germany hadn’t done anything worse than many other nations. This is a great article and eye opening! I loved the walking tour in Berlin and am fascinated by WW2 history so it was just the perfect day learning everything, although so much sadness happened. I think it’s great that Berlin doesn’t hide the history at all.

Rachel of Hippie in Heels recently posted..When to Travel to India: Everything You Need to Know

Oh, that’s weird. I feel like most Germans I’ve talked to, and the overall feeling I got in Berlin, felt the opposite of him. The US has done some pretty horrible things that are rarely talked about at home, but I think it’s pointless to compare who has done the worst instead of focusing on how we can overcome the past and change the future. But I agree, the walking tour I went on was a great introduction to the city!

Berlin has been on my list for ages because of the historical aspect of the city, so I find this article quite interesting. Great job writing it!

Personally, I think seeing the monument can be a reminder not only of the past, but also how far they have come as a country. The past can’t be re-written, only learned from, and I think the German people have worked hard to do just that.

Estrella recently posted..My Favourite Cafes in Malasana

Thanks, Estrella! I like how you look at it as a gauge of how far they’ve come. I hope you get to visit Berlin soon- it’s an amazing city!

I love the fact Germans are so open-minded when it comes to talking about the past. My father is half German and I used to spend a lot of time in Berlin, reading and experiencing the history of this city. Great memories! I’m back in the city in 8 weeks.

Agness recently posted..Breakdown Of Our Costs In Singapore

It is nice to be in a place that recognizes their own past, mistakes or otherwise. Enjoy your time in Berlin!

Hmm. Well, I think for… where Germany was not that long ago, they have recovered spectacularly. However, I do think it’s a hard thing to swallow and live with — especially as the main perpetrators of unimaginable horrors. To be honest, I think most of the world has done a great job at letting it go and allowing Germany to rebuild given what actually went down. I mean, the Holocaust is more than a stain on history… it is a systemic tragedy that… I don’t even have words to express. To be honest, I didn’t speak about it much with my German friends, but I know when I visited the memorial in Berlin, I think us Americans were a little more somber and reserved than they were. It just was something that was there to them, just some statues to be walked through. And I can’t say what they felt inside, but I think there’s a big dissociation with it, a separation from it. But too much of that (“oh, it was a different generation”) can be dangerous, too. Yes, you must move on but you must never forget and you must always look for ways to prevent it. I think that’s why German patriotism may never quite take off. The last time they were truly proud of their country on a wide, fierce level, it involved a lot of destruction. I think giving into that patriotism for them may represent a slippery slope and is probably why it’s avoided.

Thank you for your thoughts and opinions, Erika! They made me think a lot. Honestly, I think patriotism is a slippery slope to begin with and I would never say that I’m proud to be an American, but a young person still feeling something along the lines of shame for something they had absolutely no involvement in seems a tad much for me. The Holocaust was a horrible thing and recognizing that and remembering it and learning from it is hugely important, but I don’t agree that it should still frame a nation’s view of itself. Germans aren’t hardwired to hate so if now, 60 years later, they are allowed to feel slightly good about Germany it’s not going to turn into another Holocaust.

I really enjoyed this post. I studied abroad in Germany during high school and agree with much of what you’ve written. I’ve definitely found that Germans are often afraid to be proud or patriotic of their country because of the past, and I’ve always been fascinated with how different generations of Germans have come to terms with it.

I’ll never forget one experience I had while studying abroad. I was in a history class at the high school I attended there. The teacher put up the Pledge of Allegiance on a projector. I wish I would have spoken more German then so I could have understood the entire discussion. Anyways, at one point in the class they asked me for my perspective on it. They wanted to know why we did it and what it meant to me. I had never even thought about it and quite honestly didn’t know how to respond. To me it was just something we did. I never really thought about what the words meant or how deeply ingrained patriotism was in my own culture. The Germans couldn’t imagine having to stand up and pledge allegiance to their country every day in school or teaching their kids to blindly do so. Given the history of how the Nazis evolved it makes perfect sense.

That was the day I began to really question my own country and the things I had been taught to believe without a doubt my entire life. Patriotism can be a beautiful and dangerous thing. It was such an interesting way to compare the two cultures and see things from another perspective.

MIQUEL recently posted..Setting Intentions

Thanks for the great comment! I agree completely that patriotism can also be very dangerous. Living and traveling abroad has really opened my eyes to how patriotism is so ingrained into American life and how strange and uncomfortable that makes me at times.

I actually hate the way certain countries sweep their mistakes of the past under the rug. Children are then only taught a biased view of their country and are made to think that theirs is the greatest, and that kind of clouded judgement is so damaging. For one thing, it’s how history repeats itself.

I guess the reminders are there to show us that we’ve owned up to our mistakes, are now acknowledging them, and are now trying to right the wrongs and pay respect to whoever may have been hurt by them. I don’t necessarily think you can’t move on when those tragedies are constantly staring you in the face – I think they help a nation improve and better themselves because they’re constantly learning and going forward with different ideas next time around.

This is a really great topic. Thank you for writing this post.

Thank you for writing this post.

Ceri recently posted..That Time I Visited Crazy Cat Lady’s House (and Other Catty Musings)

I agree with you, Ceri. It sickens me the way the US ignores basically all of the mistakes we as a country have made, so I definitely respect the way Germany is so open about their troubled past. And I do agree with you, constantly learning is a good thing!

The aerial view of the Holocaust memorial left me speechless — it truly resembles a cemetery more than anything else..Germany has been repenting of its Nazi past since the war ended and it seems to me they will seek some kind of closure forever..which is quite sad.

I agree, Julie!